Divorce ranches, the Reno Cure, and how no-fault divorce laws upended an entire industry

But also, how much has really changed?

I recently read The Divorcées by Rowan Beaird, a fictional story about a divorce ranch in Reno and the women who stayed there. The book was decent, but the true stories behind divorce ranches sent my mind spinning and I immediately went down a rabbit hole (ADHD hyper-fixation, anyone?).

Today’s piece is what came out of that rabbit hole - the questions I had, the questions I’m still left with, and the disappointing reality that divorce for women in the 1930’s and 1950’s really isn’t all that different from today.

First, a brief history of divorce ranches….

Nevada is known for gambling and quickie marriages, but before that they were known for the quickie divorce. Seeking ways to infuse money into their state economy during and following the Great Depression in the 1930’s, Nevada shortened its residency requirements for divorce to 6-weeks and opened up a variety of avenues for people to justify their divorce that didn’t require the same burden of proof as other states (such as proving adultery, impotency, or other “faults”).

The combined effect of having the shortest-residency requirements in the nation and the ability to divorce with, while not no-fault, more lenient reasons, was that people from around the country (and even the world) flocked to Nevada.1

Unsurprisingly, most of them were women.

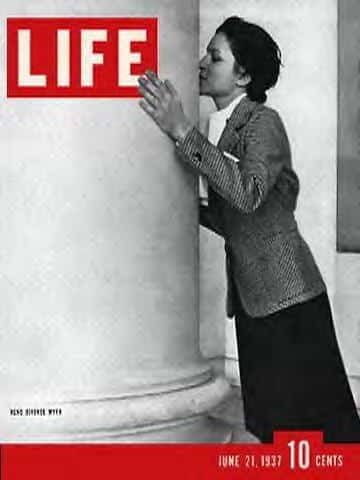

And so, a new booming industry was born, particularly in Reno, where the whole process was dubbed the Reno Cure. Over the years, ranches were repurposed, garages were renovated, homes were opened up, developers came to town, hotels were built, and local jobs ranging from ranch hands to lawyers were created to serve and refer clientele that included a plethora of people whose names we will never know to (reportedly) Arthur Miller, Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, and Gertrude Platte, who brought Eleanor Roosevelt along.

It was, if you rely on most of the easily-accessible information, all a delightful experience. One could laze about by the pool, grab drinks, go horseback riding and hiking, or spend evenings gambling downtown. Romances (and even marriages) with ranch hands were not unheard of.

If you already had a second husband lined up (oftentimes called cousins), you could bring him to town, too. Friendships were formed, as they often are during times of crisis, and communities were built. It was, by all accounts, a great place to hunker down for 6 weeks.

And it was, if you had the means and were white.

But not everyone had the money to pay for the nicer places, nor were they allowed to.

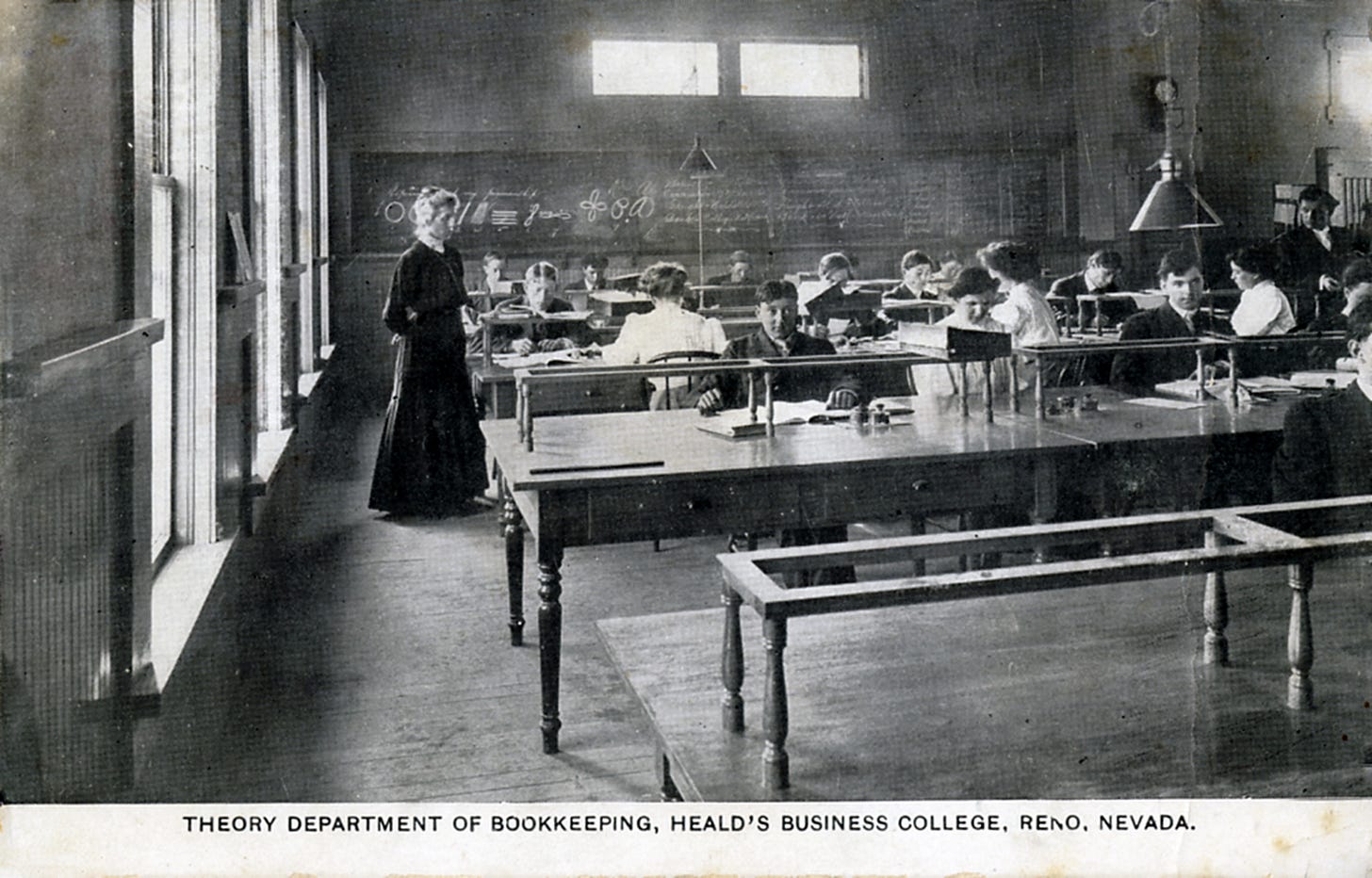

Many (both men and women) took up temp jobs ranging from mechanics to stenographers, while others enrolled in professional or secretarial schools in the hopes of leaving with a marketable skillset.

Black divorce-seekers had far fewer options, with segregation remaining legal in Reno, also called ‘the Mississippi of the West’, until 1959. Non-legislated segregation persisted into the 1960’s, requiring divorce-seekers to have a connection to and reliance on the local community’s support system to navigate the city and the process. (The hub for this process was the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which had a boarding house next door).

A fair number of children also accompanied their parents, which surely left a lasting impact on those who were old enough to remember it, both the kids who came and the local kids who watched friends come and go.

And I could find little about what happened to women, particularly moms, when they left, whether they were able to tough it out as a single mom in a time when they didn’t even have access to a credit card or bank account, or if they ended up in less than ideal situations just to survive.

Regardless, the Reno Cure disappeared practically overnight after access to divorce expanded in 1969, when then-California Governor Ronald Reagan signed the country’s first no-fault divorce law, which quickly spread nationwide.

No-fault divorce laws resulted in a 20% decline in overall female suicide rates, a decline in domestic violence and murder of women, and increased the bargaining power of the dissatisfied spouse.

Bargaining in the Shadow of the Law: Divorce Laws and Family Distress by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers

//

If I’m being totally honest, when I first read about divorce ranches, I thought, oh, that would have been great when I was getting divorced a couple of years ago. Six weeks to rest and recharge and plan without any distractions? What a dream!

But of course, a divorce ranch wouldn’t have been in the cards for me because to go would have meant having a plethora of resources that I didn’t, and don’t, have.

I’ve touched before on the privilege required to leave a marriage by choice (and will again), so naturally I had some questions about how this all worked:

Who was watching the kids, if they had them? Or, if they brought them with them, what was the childcare situation while they were at work?

Who was paying for their stay? (This was the 1930’s - 60’s, mind you, so most women didn’t have thousands of dollars at their disposal)

What happened when they left? How many were able to make it long-term, economically, as a single women?

How many ended up in second marriages simply because it was easier and more economically advantageous to be partnered?

What was the social stigma like for them?

How many were there because their divorce was mutually agreed-upon versus women fleeing abusive ones?

Because going to Nevada, especially for those from the East Coast, also meant privilege. It assumed you could afford the cost of travel and boarding, that childcare was taken care of, that you had resources to live on your own, that you were mentally able to sustain the social stigma placed upon you.

And if you didn’t have these things, it meant you had the confidence that it would all work out, a mindset that is also in and of itself a privilege.

Being hyper-aware of today’s social, political, and economic realities for women, I couldn’t help but notice that this list is largely the same today as it was nearly 100 years ago, and the result is a whole lot of people legally trapped in marriages they’d rather not be in.

Even setting aside the very obvious fact that most of us cannot afford to jet off somewhere for 6 weeks without any distractions or responsibilities tethering us to home, the barriers to divorce remain very much the same even on a day-to-day basis, and even with no-fault in effect.

It is, of course, much more acceptable for women to work these days (mostly, that is, although the trad wife movement would likely disagree), but even so, childcare is extremely cost-prohibitive, not to mention there’s no guarantee of a spot. Too many jobs don’t pay a living wage and those that do oftentimes don’t provide paid leave or flexible work schedules or locations, not to mention there’s the motherhood penalty to contend with. Housing costs are astronomical with little protections for renters, so going it solo means taking on the full financial burden, but also solely taking on the risk that comes with it. The list goes on.

And yet, despite all of this, women are far more likely to initiate divorce, and do so at much higher rates than men.

Many men hate this, of course, particularly those who would prefer to continue benefitting from their partner’s unpaid physical and emotional labor, or in more severe cases, continue wielding their power and control in abusive ways.

It’s this desire to benefit off of and control women that’s behind the current push to end no-fault divorce and, more broadly, the laws intended to control and contain women.

Because let’s be real - if you have enough resources, you will still get what you want and/or need.

Strict divorce laws around the country in the 1950’s didn’t stop women from pursuing divorces in Nevada (or men from paying for divorces they wanted), it just prevented women who lacked resources from obtaining one in their home states.

Because if your husband was abusive and didn’t want a divorce, he wasn’t going to let you go to Reno without a fight.

If your religious Dad believed you were only whole once you became a man’s wife, he probably wasn’t helping out by watching the kids or providing emotional support.

If your job didn’t offer 6 weeks of time off, you probably weren’t quitting your job for it.

If you didn’t have a job at all, getting the funds to head to Reno probably wasn’t in the cards, either.

If you didn’t have a “valid” reason to get a divorce in your home state and also couldn’t afford to travel to NV, you probably weren’t getting divorced.

And really, this is all still true today, only with a few minor changes:

If your husband is abusive and doesn’t want a divorce, he will probably still fight you on it and will use the system to his advantage, not to mention weaponize your kids.

If your religious Dad believes you are only whole once you become a man’s wife, he’s still not going to help you out by watching the kids or providing emotional support.

If your job doesn’t offer time off (never mind paid), you’re probably still not quitting your job to make the time to do the legal paperwork.

If you don’t have a job or income, then paying the fees associated with a divorce is probably going to be pretty difficult and still may not be in the cards.

If you’ve internalized the messaging that a marriage needs to be “bad enough” to leave, that you need a “valid” reason, then you’re probably going to stay in a marriage you’d prefer to leave but give a variety of excuses to justify it.

Of course, there are simple policy solutions that would allow women to gain more economic freedom, freedom that would grant them more choices. From universal childcare and healthcare to paid leave to flexible work arrangements to ending the motherhood penalty and pink taxes, states around the country are passing laws that increase protections and access to resources.

But at the same time, there’s a push to either roll back these policies or prevent them from passing in the first place.

And while most politicos don’t think it’s very likely that states will rollback no-fault divorce laws en masse, I can’t help but wonder what kinds of “ranches” will pop up in the next several years as women are, once again, forced to cross state lines to access basic services pertaining to their personal life, such as abortion.

(If you’re not following , now is a good time to do so. And maybe also Google the Jane Collective, while you’re at it).

//

Which is all a really long way of saying that the book was decent, my curiosity about the true stories behind the book sent me down a rabbit hole, and now I’m sad and angry about how many women still can’t get the divorce they want (which to be fair is my usual state of being) and have to worry about whether that access will get even harder in the coming years.

Probably not the takeaway the author was hoping for when she wrote The Divorcees, but hey, this is how my brain works.

(PS: I’m currently reading I Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation by

, so I can’t wait to see what I’m thinking when I finish that one up!)

Thank you for reading! If you liked this post, please consider subscribing for free, sharing with a friend, or becoming a paid subscriber to support my work.

Not all states wanted to recognize it, though, with Illinois being the first to challenge it and Maryland refusing to recognize them