Social media, children's privacy, and how to ask others to respect your boundaries

Setting boundaries can be awkward, but it's worth it

Buckle up, this is a long one as I dig into the why and how I chose not to post my son’s face or personally identifiable information on social media.

If you just want to see the tips for navigating this discussion, feel free to scroll right on by to the list at the end, complete with prompts for paid subscribers. I promise I won’t be (too) offended.

I don’t post my son on the Internet.

At least not his face, and certainly not any identifiable information. I don’t post his name and although my general due date was rather public, I don’t post about his birthday in real-time, either. Thankfully, there was not much follow-up after I had him, in part, I’m sure, because it didn’t even occur to me to send the details and photos to our local newspaper, but also because it was the early days of the pandemic and things were a little overwhelming, as it was.

Over the years, people have had various reactions to my choice, but in the last year or so I have noticed a marked shift towards understanding it and respecting it, whereas five years ago I was met with, at best, supportive skepticism, and at worst, outright disdain.

I was told I was overreacting, that it was selfish not to share, that my concerns about AI and big data and privacy were overblown, that everything was fine, it was no big deal. That because I can’t control every photo at every birthday party or school event, there’s no point in trying, so what’s the problem?

But I remained steadfast in my commitment, in large part because of what I am going to write about today, but also because enough people were publicly awful to me about my choice to become a mom in the first place that they frankly didn’t deserve access to my son or my joy.

To be fair, my close family and friends were supportive, even if they didn’t get it. To this day, they don’t post his face, they don’t use his name, and they don’t tag me in anything. The few times they have, I’ve asked them to delete it and not only did they do it without any fanfare, but they are still my friends.

The world did not end.

It’s only been an issue twice. Once when a babysitter we’d had for a long time, who was also a teacher at his school, posted him on her personal Facebook, knowing full well how I felt about it, something I only learned about because another mom saw it and flagged it. She took it down, but the relationship ended fairly soon after, for a variety of reasons. The other, I’d prefer not to get into.

So why don’t I post him online?

There are a few reasons for this.

In 2016, I was already skeptical about big data and AI, having worked on the policy side about how to leverage it for better decision-making. When I started digging into it, it was a side project that my boss at the time indulged, a request I had made because it was interesting and I could see the implications, even though it didn’t fall under the scope of my work. He was skeptical.

A year later, big data was a big deal.1

On the flip side, this also taught me how massive amounts of data can be combined to build profiles of people, which can be great if de-identified and used to deliver services, but not so great if say, the inputs are rooted in racism and inequality or a tech billionaire gains access to those systems and wades into all of your personal business to make decisions about who gets what and when.

And then there’s the surveillance state and what I learned by talking with our police department and others in law enforcement, the tools they have at their fingertips to track and monitor us, despite ongoing complaints that it’s not enough and more money is needed to do even more surveillance. From red light cameras to social media monitoring software to UAV’s to video surveillance to license plate readers, not to mention their partnerships with Ring, not much of what we do is private.2

And before you say, well if you don’t do anything wrong, what’s to worry about?, let me tell you about Clearview AI, a U.S.-based software that scrapes the internet for everything about you (and your children), whether or not you deleted it, to build a profile, and then they granted access to that facial recognition tech to schools, law enforcement, local governments, federal agencies, and industries such as retail, gaming, and banking. They also marketed their product to governments with authoritarian regimes, not to mention the White House/Congress was involved back in 2020.

Since then, they have been probed by Congress, were forced to stop collecting data in Canada, and settled cases with Illinois in 2024 (for violating its biometric law) and with the ACLU and other groups in 2022.

Yet, they’re still around and still very much in business.

Which is all to say, I’ve learned over the years that most of my “unreasonable and panicky” concerns about technology and information have proven to be, in fact, reasonable and sane.

So while many may trust tech companies to adhere to a moral code, I do not and am wary of giving any child over to a technology that could be turned into a phone app where someone on the street can take their picture and find out everything about them - their full name, where they live, where they like to shop, where they go to school - not to mention age progression technology means a lifetime of access.

“Among the concerns raised by Tortolero’s group was that photos posted on social media sites such as Facebook or Instagram, and turned into a “faceprint” by Clearview, could end up being used by stalkers, ex-partners or predatory companies to track a person’s whereabouts and social activity.” - Linda Xochitl Tortolero, president of Chicago-based Mujeres Latinas en Accion, a plaintiff in the case against Clearview AI

For their part, teens do not trust big tech companies.

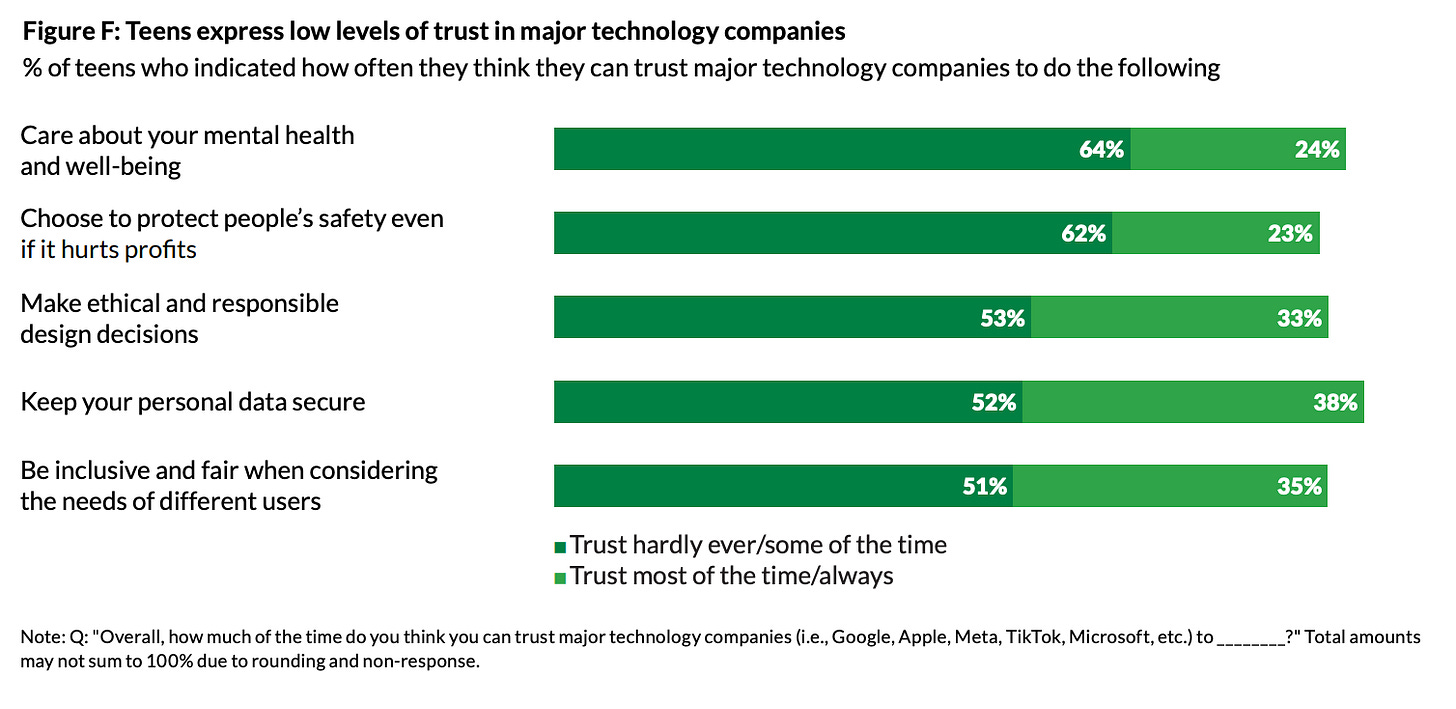

A recent study, Teens, Trust, and Technology in the Age of AI: Navigating Trust in Online Content, from Common Sense showed that teens today don’t trust big tech to make responsible decisions, finding:

“Slightly over half of teens report that they have low levels of trust in major technology companies to make ethical and responsible design decisions (53%), keep teens' personal information secure (52%), or be inclusive and fair when considering the needs of different users (51%).

In regard to AI, nearly half (47%) of teens have little to no trust that tech companies will make responsible decisions about how they use AI.”

And also,

“Around 6 in 10 teens say that major technology companies (i.e., Google, Apple, Meta, TikTok, Microsoft, etc.) cannot be trusted to care about their mental health and well-being (64%) or to protect people's safety even if it hurts profits (62%).”

But us millennial moms?

We are chronically online and oversharing, oftentimes even when we don’t trust it. I’m doing it right now, as I sit at my computer and write yet another essay that draws on my personal life, which I will then put out into the world. I will do it again later when I post some fun photos of my weekend.

This is partly because it’s habit, but also because my life is already so very public.

For us elder millennials, in particular, social media arrived as we took our first steps into adulthood, when it was fun and exciting and new. Even for younger millennials, it was a novelty. There were no sophisticated phone apps to mine your data, or fancy softwares to target ads based on that data collection.

Photos were still mostly candid, the goal was to show how much fun you had, not craft some perfect version of motherhood or marriage or travel or whatever we are selling these days. And we certainly weren’t using up valuable phone storage to take a 17 minute video at a concert. Instead, we were using shitty sepia filters on our grainy photos on Instagram, not giving any thought to our grid layouts or going viral.

And, let’s be real, a lot of us like the validation. We like the likes and the shares and the comments because it validates our choices, our worth. Even when we work hard to separate our worth from our achievements, we wouldn’t be sharing and posting and writing online if there wasn’t at least a small part of us that wanted it, was thrilled by it, felt that it made a difference, made us feel useful in some way.

And to be fair, we, as in society, need people like this. We need them to build community, to tackle tough issues that are spoken about in hushed tones, to hold our elected officials accountable in a way that is public, to break down complex topics into easily digestible bites, to put themselves out there for the greater good.

But when it comes to our kids, as a whole, we can take it too personally. When people compliment our child, or praise our parenting skills, or comment on our great activity idea, online or off, they are in a way validating us. Not our kids, who probably don’t notice or care about said comments, but us.

And we notice.

And so we continue to post, with many of us unable to completely pull back. Sure, I stopped being active on Facebook a long time ago and post less on Instagram, but now I write here, so I’m not so much sharing less as I have changed the content and the medium.

And for me, that’s fine. I’ve already built a public reputation, the apps already have my data, and the algorithms are already pretty good. So while I do try to engage in good digital hygiene, such as turning off certain features and updating settings and so on, I know I’m a lost cause.

My son, however, is not.

And this brings me back to why I don’t post his face or personally identifiable information online.

I know that predators pull photos of kids from Instagram and use them for nefarious purposes using AI.3

I also know that my heart would break if, when he got older, my son told me he didn’t want to be online all those years, that he felt pigeon-holed into my version of what his childhood should look like, felt like he had to live up to the persona I’d created for him.

Or worse, that the lesson he’d learned was that we must hide the messiness of our minds and lives in order to “present well” to strangers we don’t know, just another iteration of teaching him to suppress his reality and emotions in order to conform to societal expectations.

And lastly, I know he’s not a product, which is what we all are when we post on social media. Even if we are not influencers exploiting our kids who are too young to properly consent, we are a product simply because we are on it in the first place, sold off to advertisers so they can boost their profits while giving up our privacy.

We don’t have to give them our kids, too.

Here is where I am supposed to say that if you post your kids’ faces all the time, I don’t judge you.

And that’s true, for the most part. But also, sometimes I do, because it’s not hard to tell who is posting a fun milestone or family event for friends and family vs. who is using their children for self-validation and “exposure”.

In other words, motive matters. Everyone has a different bar for what they’re comfortable with, but I also think a lot of people are uncomfortable digging into and recognizing their why for posting in the first place.

This includes me. When I say I’m judging, I also mean I’m judging myself.

For example, my Instagram account used to be heavily nature-focused (nowadays it’s essentially nature, my essays here, and current events as they pertain to women and moms). Even though I didn’t post his face, I would post photos of all of our hikes, the look at this view! images that made it look like all hikes were amazing, getting the warm and fuzzies when people commented on how great it was that we got outside so much, that I was such a great mom.

And hiking was - is - great. Nothing has changed about our love for nature, but I no longer feel the need to make that our entire personality on his behalf on a public platform he may or may not want to be part of later because I like the likes (and I wasn’t even making money off of it!). Now, I save the photos for the photo albums and the hikes are more fun because I’m not worried about getting the right shot.

Which is to say, I am glad to see so many other moms learn about the scary side of the Internet and scale back what they post. Major influencers whose currency is motherhood are scrubbing photos with their children’s faces from their profiles, or removing them altogether. Regular moms like me are also taking a step back from sharing, whether by posting less frequently or altogether.

And if you fall into this latter camp of wanting to share your kids’ faces online less but aren’t sure how to approach this with others, here are a few things that have worked for me.

Be firm in your request

Know your limits

Get comfortable with discomfort

Don’t be afraid to ask people to take things down after the fact

Know that you do not necessarily have to give up your right to privacy to attend events where there are photographers

Find a way to share that works for you

Although this list is free to read, suggested prompts, including what I have personally used, are available for paid subscribers. Subscribe now for full access.